The Rural-Urban Divide: Family Social Capital, Family Cultural Capital, and Educational Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents

Abstract

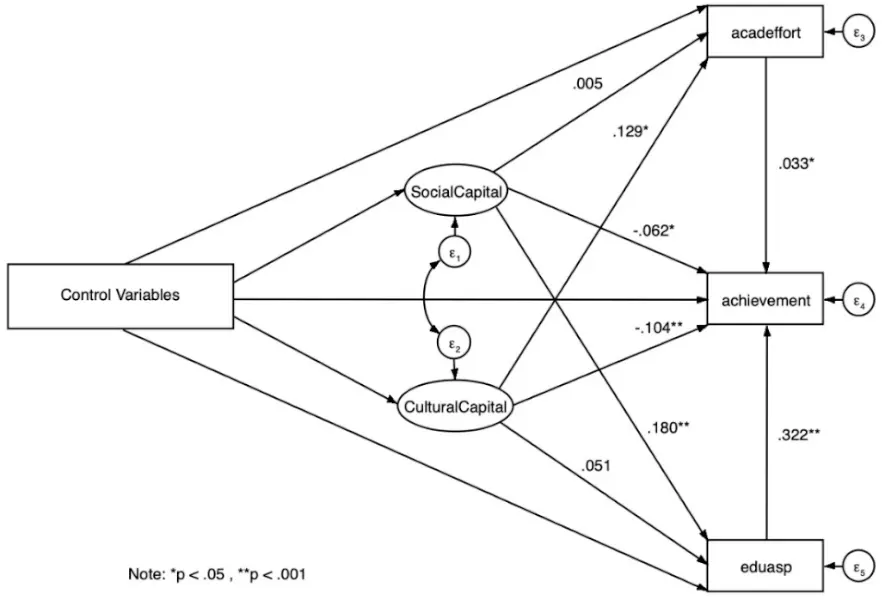

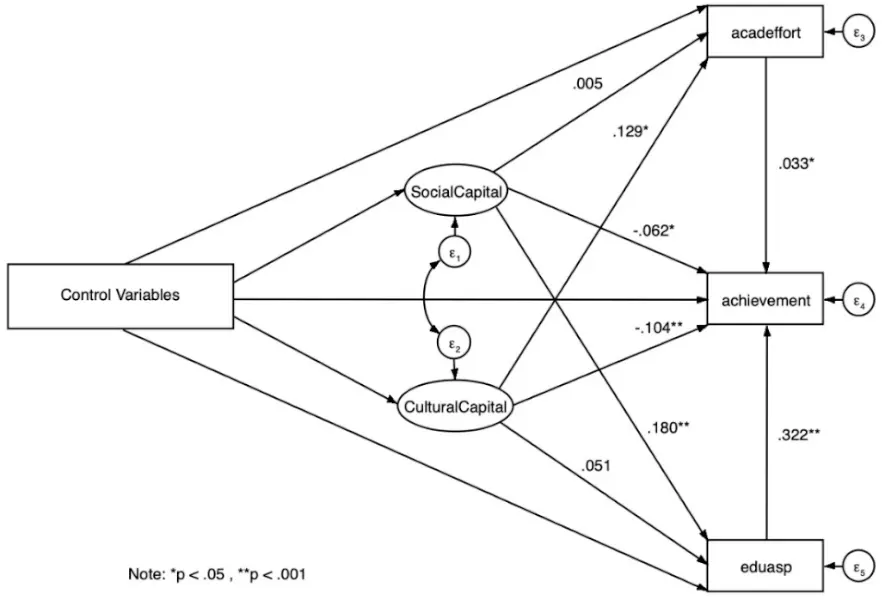

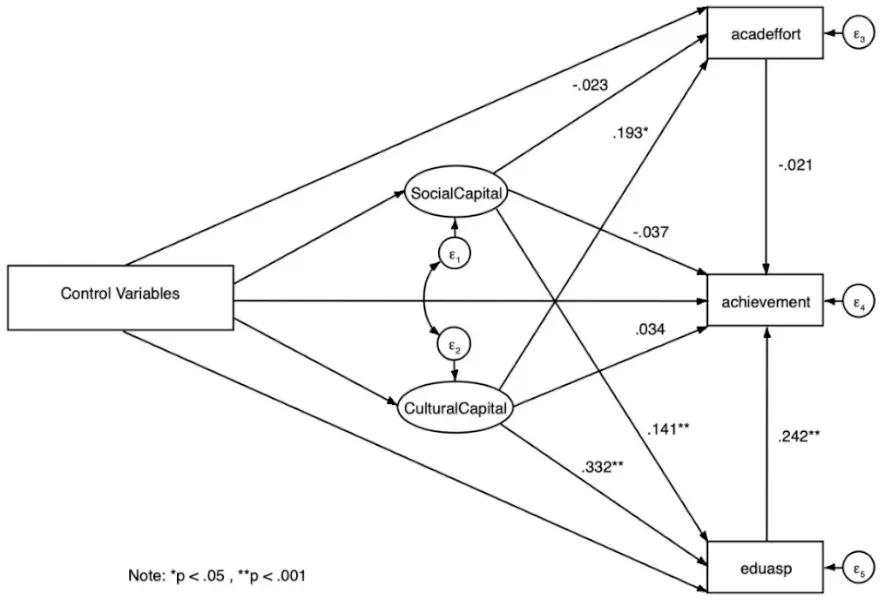

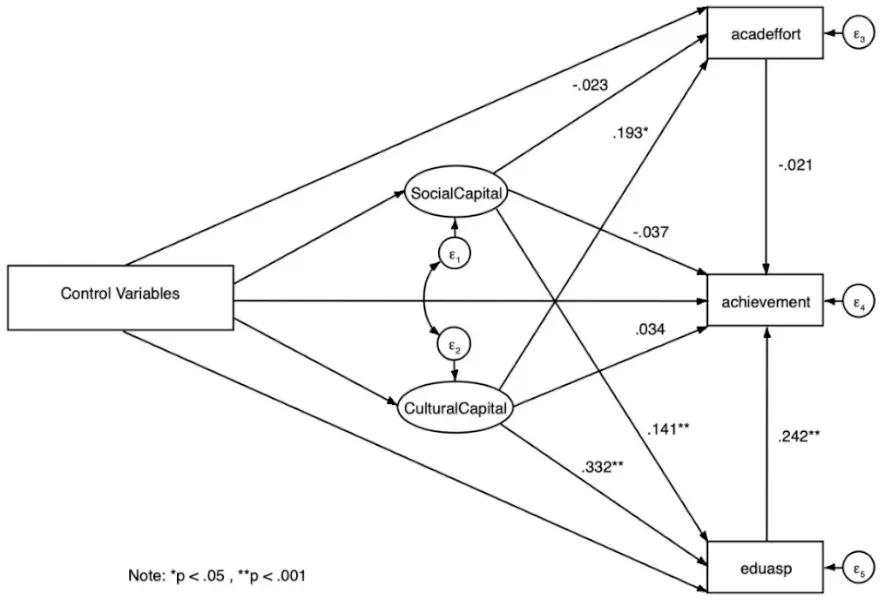

A large body of research has been dedicated to the study of relationships between social or cultural capital and educational outcomes in Western countries. However, few studies have examined these associations in a Chinese context, and even fewer have examined the effects of both forms of capital on educational outcomes simultaneously within a familial context in China. This study offers a reformulation of the associations between family social capital and family cultural capital on the educational outcomes of adolescents in both rural and urban China. Using the structural equation modelling approach and the China Education Panel Survey, this study sheds some new insights – the presence of significant compositional differences in both family social capital and family cultural capital between rural and urban Chinese adolescents, and differential effects of both forms of capital on educational outcomes were found. Family social capital presented larger positive effects on the academic effort and educational aspiration of rural adolescents while having no positive effects in facilitating the academic achievement of both rural and urban adolescents. Meanwhile, family cultural capital presented larger positive effects for urban adolescents on all educational outcomes as compared to their rural counterparts.

Cite This Paper

Tan, C. G. L., & Fang, Z. (2023). The Rural-Urban Divide: Family Social Capital, Family Cultural Capital, and Educational Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Economic Analysis, 2(2), 27. doi:10.58567/jea02020006

Tan, C. G. L.; Fang, Z. The Rural-Urban Divide: Family Social Capital, Family Cultural Capital, and Educational Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Economic Analysis, 2023, 2, 27. doi:10.58567/jea02020006

Tan C G L, Fang Z. The Rural-Urban Divide: Family Social Capital, Family Cultural Capital, and Educational Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Economic Analysis; 2023, 2(2):27. doi:10.58567/jea02020006

Tan, Claire G. L.; Fang, Zheng 2023. "The Rural-Urban Divide: Family Social Capital, Family Cultural Capital, and Educational Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents" Journal of Economic Analysis 2, no.2:27. doi:10.58567/jea02020006

1. Introduction

2. Hukou Registration and Rural-Urban Educational Inequality in Chinese Society

3. Data and Empirical Methodology

4. Results and discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding Statement

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

Author contributions

Notes

References

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238-246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: Sage. [Google Scholar ]

- Brown, T. A., & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modelling (pp. 361-379). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar ]

- Chan, K., & Zhang, L. (1999). The hukou system and rural-urban migration in China: Processes and changes. The China Quarterly, 160, 818-855. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000001351 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Chesters, J., & Smith, J. (2015). Social capital and aspirations for educational attainment: a cross-national comparison of Australia and Germany. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(7), 932-949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.1001831 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Covay, E., & Carbonaro, W. (2010). After the bell: Participation in extracurricular activities, classroom behavior, and academic achievement. Sociology of Education, 83(1), 20-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040709356565 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Crosnoe, R. (2004). Social capital and the interplay of families and schools. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66(2), 267-280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00019.x [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- De Graaf, N. D., De Graaf, P. M., & Kraaykamp, G. (2000). Parental cultural capital and educational attainment in the Netherlands: A refinement of the cultural capital perspective. Sociology of Education, 73(2), 92-111. doi:10.2307/2673239 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- DiMaggio, P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on the grades of US high school students. American Sociological Review, 47(2), 189-201. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094962 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Duan, W., Guan, Y., & Bu, H. (2018). The effect of parental involvement and socioeconomic status on junior school students’ academic achievement and school behavior in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(952), 1-8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00952 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Dufur, M. J., Parcel, T. L., & Troutman, K. P. (2013). Does capital at home matter more than capital at school? Social capital effects on academic achievement. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 31, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.08.002 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Fan, J. (2014). The impact of economic capital, social capital and cultural capital: Chinese families’ access to educational resources. Sociology Mind, 4, 272-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2014.44028 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Fleisher, B. M., & Yang. D. T. (2003). Labor laws and regulations in China. China Economic Review, 14, 426-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2003.09.014 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Fu, Q., & Ren, Q. (2010). Educational inequality under China's rural–urban divide: The hukou system and return to education. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(3), 592-610. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42101 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Hango, D. (2007). Parental investment in childhood and educational qualifications: Can greater parental involvement mediate the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage? Social Science Research, 36(4), 1371-1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.01.005 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Hanushek, E. A. (1992). The trade-off between child quantity and quality. Journal of Political Economy, 100(1), 84-117. https://doi.org/10.1086/261808 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Jæger, M. M. (2009). Equal access but unequal outcomes: Cultural capital and educational choice in a meritocratic society. Social Forces, 87(4), 1943-1971. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0192 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Jæger, M. M., & Møllegaard, S. (2017). Cultural capital, teacher bias, and educational success: New evidence from monozygotic twins. Social Science Research, 65, 130-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.04.003 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Kalmijn, M., & Kraaykamp, G. (1996). Race, cultural capital, and schooling: An analysis of trends in the United States. Sociology of Education, 69(1), 22-34. doi:10.2307/2112721 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Katsillis, J., & Rubinson, R. (1990). Cultural capital, student achievement, and educational reproduction: The case of Greece. American Sociological Review, 55(2), 270-279. doi: 10.2307/2095632 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Kaufman, J., & Gabler, J. (2004). Cultural capital and the extracurricular activities of girls and boys in the college attainment process. Poetics, 32(2), 145-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2004.02.001 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Khodadady, E., & Zabihi, R. (2011). Social and cultural capital: Underlying factors and their relationship with the school achievement of Iranian university students. International Education Studies, 4(2), 63-71. doi:10.5539/ies.v4n2p63 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Kilpatrick, S., & Abbott-Chapman, J. (2002). Rural young people’s work/study priorities and aspirations: The influence of family social capital. The Australian Educational Researcher, 29(1), 43-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219769 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Kim, D. H., & Schneider, B. (2005). Social capital in action: Alignment of parental support in adolescents’ transition to postsecondary education. Social Forces, 84(2), 1181-1206. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0012 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar ]

- Kwong, J. (2004). Educating migrant children: Negotiations between the State and Civil Society. China Quarterly, 180, 1073-1088. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574100400075X [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Lee, H. (2022). What drives the performance of Chinese urban and rural secondary schools: A machine learning approach using PISA 2018. Cities, 123, 103609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103609 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Liang, Z., & Chen, Y. P. (2007). The educational consequences of migration for children in China. Social Science Research, 36(1), 28-47. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812814425_0009 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Li, H., Zhang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2008). The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: Identification using Chinese twins. Demography, 45(1), 223-243. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2008.0006 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Ma, G., & Wu, Q. (2020). Cultural capital in migration: Academic achievements of Chinese migrant children in urban public schools. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105196 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Marjoribanks, K. (1997). Family background, social and academic capital, and adolescents' aspirations: A mediational analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 2(2), 177-197. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009602307141 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Marjoribanks, K., & Kwok, Y. (1998). Family capital and Hong Kong adolescents' academic achievement. Psychological Reports, 83(1), 99-105. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.83.1.99 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Mendez, I. (2015). The effect of the intergenerational transmission of noncognitive skills on student performance. Economics of Education Review, 46, 78-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.03.001 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Ministry of Education. (1995, March 18). Education Law of the People’s Republic of China. Retrieved from http://en.moe.gov.cn/Resources/Laws_and_Policies/201506/t20150626_191385.html [Google Scholar ]

- Ministry of Education (2020). Overview of educational achievements in China in 2019. Retrieved from http://en.moe.gov.cn/Documents/Reports/202102/t20210209_513095.html [Google Scholar ]

- Qian, X., & Smyth, R. (2008). Measuring regional inequality of education in China: Widening coast-inland gap or widening rural-urban gap? Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 20(2), 132-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1396 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Roscigno, V. J., & Ainsworth-Darnell, J. W. (1999). Race, cultural capital, and educational resources: Persistent inequalities and achievement returns. Sociology of Education, 72(3), 158-178. doi:10.2307/2673227 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Sandefur, G. D., Meier, A. M., & Campbell, M. E. (2006). Family resources, social capital, and college attendance. Social Science Research, 35(2), 525-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.11.003 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Schlee, B. M., Mullis, A. K., & Shriner, M. (2009). Parent social and resource capital: Predictors of academic achievement during early childhood. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(2), 227-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.07.014 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Shahidul, S. M., Karim, A. H. M., & Mustari, S. (2015). Social capital and educational aspiration of students: Does family social capital affect more compared to school social capital?. International Education Studies, 8(12), 255-260. doi:10.5539/ies.v8n12p255 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Smith, M. H., Beaulieu, L. J., & Israel, G. D. (1992). Effects of human capital and social capital on dropping out of high school in the South. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 8(1), 75-87. Retrieved from http://sites.psu.edu/jrre/wp-content/uploads/sites/6347/2014/02/8-1_6.pdf [Google Scholar ]

- Smith, M. H., Beaulieu, L. J., & Seraphine, A. (1995). Social capital, place of residence, and college attendance. Rural Sociology, 60(3), 363-380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1995.tb00578.x [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Tramonte, L., & Willms, J. D. (2010). Cultural capital and its effects on education outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 200-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.06.003 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Wang, D. (2008). Family-school relations as social capital: Chinese parents in the United States. The School Community Journal, 18(2), 119-146. Retrieved from http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/133036 [Google Scholar ]

- Wu, X. (2011). The household registration system and rural-urban educational inequality in contemporary China. Chinese Sociological Review, 44(2), 31-51. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555440202 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Wu, X., & Treiman, D. J. (2004). The household registration system and social stratification in China: 1955-1996. Demography, 41(2), 363-384. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0010 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Wu, Q., Tsang, B., & Ming, H. (2012). Social capital, family support, resilience and educational outcomes of Chinese migrant children. British Journal of Social Work, 44(3), 636-656. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs139 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

- Zhang, J. (2017). The evolution of China's one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 141-160. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.1.141 [Google Scholar ][Crossref]

| Variable | Definition | Survey question | Coded response |

| Family Social Capital | |||

| parinv | Parental involvement |

(1) How often did your parents check up on your homework last week? (2) How often did your parents give instruction on your homework last week? |

0 (Never) 1 (One or two days) 2 (Three or four days) 3 (Almost every day) * Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.77 |

| pcdiscussion | Parent-child discussion | (1, 2) How often does your Mother/ your Father discuss things that happened at school with you?(3, 4) How often does your Mother/ your Father discuss the relationship between you and your friends?(5, 6) How often does your Mother/ your Father discuss the relationship between you and your teachers? |

0 (Never) 1 (Sometimes) 2 (Often) * Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.82 |

| pcinteraction | Parent-child interaction | How often do you read with your parents? |

0 (Never) 1 (Once a year) 2 (Once every half year) 3 (Once a month) 4 (Once a week) 5 (More than once a week) |

| parexp | Parental expectation | What is your parents’ requirement on your academic record? |

0 (No special requirement) 1 (About the average) 2 (Above the average) 3 (Be one of the top five in class) |

| Family Cultural Capital | |||

| dialect | Dialect | What language do you usually speak with your parents? |

1 (Dialect of my hometown) 2 (Sometimes dialect of my hometown, sometimes Mandarin Chinese) 3 (Mandarin Chinese) |

| owndesk | Own desk | Do you have a writing desk of your own at home? |

0 (No, I don’t) 1 (Yes, I do) |

| ownbooks | Own books | How many books do your family own? (not including textbooks or magazines) |

1 (Very few) 2 (Not many) 3 (Some) 4 (Quite a few) 5 (A great number) |

| highedum | Mother’s educational attainment | What is the highest education level your Mother has completed? |

0 (None) 1 (Finished elementary school) 2 (Junior high school degree) 3 (Technical / Vocational school degree) 4 (Senior high school degree) 5 (Junior college degree) 6 (Bachelor degree) 7 (Master degree or higher) |

| higheduf | Father’s educational attainment | What is the highest education level your Father has completed? | |

| Educational Outcome | |||

| acadeffort | Academic effort | How much time did you spend on homework assigned by your teachers at school last week? |

0 (0 hour) 1 (Less than 1 hour) 2 (About 1-2 hours) 3 (About 2-3 hours) 4 (About 3-4 hours) 5 (About 4-5 hours) 6 (About 5-6 hours) 7 (About 6-7 hours) 8 (About 7-8 hours) 9 (More than 8 hours) |

| eduasp | Educational aspiration | What is the highest level of education you expect yourself to receive? |

0 (I don’t care) 1 (Drop out now) 2 (Graduate from junior high school) 3 (Go to technical secondary school or technical school) 4 (Go to vocational high school) 5 (Go to senior high school) 6 (Graduate from junior college) 7 (Get a Bachelor degree) 8 (Get a Master degree) 9 (Get a Doctor degree) |

| achievement | Academic achievement | Exam marks for English, Mathematics and Chinese obtained during the mid-term of Academic Year 2013-2014 | *Standardised to a mean of 70 and standard deviation of 10, and summed into a single score |

| Control variable | |||

| Age | Your date of birth is: | YYYY/MM | |

| Gender | Your sex is: | 0 (Male); 1 (Female) | |

| Ethnicity | Your ethnic nationality is: | 0 (Minority); 1 (Han) | |

| Family structure | Which of the following people live in the same household with you at present? |

0 (Other family arrangement) 1 (Child living with both parents) |

|

| Number of siblings |

(1) Are you the only child of your family? (2) How many FULL or HALF siblings do you have? |

0 (No siblings) to 5 (5 or more siblings) | |

| Financial condition | Which one of the following best describes the financial conditions of your family at present? |

1 (Very poor) 2 (Somewhat poor) 3 (Moderate) 4 (Somewhat rich) 5 (Very rich) |

|

| Cognitive ability | *Standardised scores on a series of comprehensive cognitive competency test questions conducted by the researchers on three dimensions of language, spatial ability, and logic | ||

| Hukou | What is the type of your Hukou at present? |

0 (Agricultural Hukou) 1 (Non-agricultural Hukou) |

|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| Family Social Capital | |||||

| parinv | 2.355 | 2.047 | 0 | 6 | |

| pcdiscussion | 6.208 | 3.152 | 0 | 12 | |

| pcinteraction | 2.185 | 2.060 | 0 | 5 | |

| parexp | 2.228 | 0.879 | 0 | 3 | |

| Family Cultural Capital | |||||

| dialect | 2.004 | 0.823 | 1 | 3 | |

| owndesk | 0.788 | 0.409 | 0 | 1 | |

| ownbooks | 3.140 | 1.196 | 1 | 5 | |

| highedum | 2.486 | 1.519 | 0 | 7 | |

| higheduf | 2.780 | 1.520 | 0 | 7 | |

| Educational Outcomes | |||||

| acadeffort | 5.650 | 2.517 | 0 | 9 | |

| eduasp | 6.650 | 1.999 | 0 | 9 | |

| achievement | 212.720 | 24.783 | 60.824 | 286.449 | |

| Control variable | |||||

| Age | 14.914 | 1.255 | 12 | 19 | |

| Gender | 0.519 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.922 | 0.268 | 0 | 1 | |

| Family structure | 0.775 | 0.418 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of siblings | 0.752 | 0.804 | 0 | 5 | |

| Financial condition | 2.978 | 0.538 | 1 | 5 | |

| Cognitive ability | 0.342 | 0.474 | 0 | 1 | |

| Urban | Rural | ||||

| No. of obs. | 4,004 | 7,707 | |||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Family Social Capital | |||||

| parinv | 2.797 | 2.127 | 2.125 | 1.966 | |

| pcdiscussion | 6.754 | 3.136 | 5.924 | 3.124 | |

| pcinteraction | 2.608 | 2.024 | 1.965 | 2.045 | |

| parexp | 2.243 | 0.856 | 2.220 | 0.891 | |

| Family Cultural Capital | |||||

| dialect | 2.416 | 0.722 | 1.791 | 0.791 | |

| owndesk | 0.949 | 0.221 | 0.704 | 0.457 | |

| ownbooks | 3.732 | 1.057 | 2.833 | 1.147 | |

| highedum | 3.550 | 1.673 | 1.933 | 1.077 | |

| higheduf | 3.838 | 1.677 | 2.230 | 1.079 | |

| Educational Outcomes | |||||

| acadeffort | 5.924 | 2.305 | 5.507 | 2.609 | |

| eduasp | 7.081 | 1.862 | 6.426 | 2.031 | |

| achievement | 214.568 | 24.184 | 211.760 | 25.038 | |

| Control variable | |||||

| Age | 14.693 | 1.162 | 15.029 | 1.286 | |

| Gender | 0.542 | 0.498 | 0.506 | 0.500 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.922 | 0.268 | 0.922 | 0.269 | |

| Family structure | 0.844 | 0.363 | 0.739 | 0.439 | |

| Number of siblings | 0.348 | 0.646 | 0.961 | 0.798 | |

| Financial condition | 3.145 | 0.510 | 2.891 | 0.531 | |

| Cognitive ability | 0.305 | 0.839 | -0.080 | 0.805 | |

| Academic Effort | Educational Aspiration | Academic Achievement | ||||||||

| Hukou Type | Predictor variables | Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total |

| Agricultural | Family Social Capital | 0.005 | no path | 0.005 | 0.180 | no path | 0.180 | -0.062 | 0.058 | -0.004 |

| Family Cultural Capital | 0.129 | no path | 0.129 | 0.051 | no path | 0.051 | -0.104 | 0.021 | -0.083 | |

| Age | 0.076 | -0.019 | 0.057 | -0.045 | -0.051 | -0.096 | -0.027 | 0.001 | -0.026 | |

| Gender | 0.103 | 0.008 | 0.111 | 0.102 | 0.005 | 0.107 | 0.218 | 0.031 | 0.249 | |

| Ethnicity | -0.042 | 0.008 | -0.034 | -0.052 | 0.006 | -0.046 | -0.002 | -0.023 | -0.025 | |

| Cognitive Ability | 0.050 | 0.029 | 0.079 | 0.207 | 0.024 | 0.231 | 0.316 | 0.050 | 0.366 | |

| Family Structure | -0.020 | 0.020 | 0.000 | -0.043 | 0.039 | -0.004 | 0.034 | -0.028 | 0.006 | |

| Number of Siblings | -0.029 | -0.033 | -0.062 | 0.048 | -0.040 | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.036 | 0.047 | |

| Financial Condition | -0.061 | 0.046 | -0.015 | -0.043 | 0.029 | -0.014 | 0.009 | -0.045 | -0.036 | |

| Non-agricultural | Family Social Capital | -0.023 | no path | -0.023 | 0.141 | no path | 0.141 | -0.037 | 0.035 | -0.002 |

| Family Cultural Capital | 0.193 | no path | 0.193 | 0.332 | no path | 0.332 | 0.034 | 0.076 | 0.110 | |

| Age | 0.188 | -0.021 | 0.167 | -0.060 | -0.075 | -0.135 | -0.017 | -0.033 | -0.050 | |

| Gender | 0.062 | 0.005 | 0.067 | 0.065 | 0.016 | 0.081 | 0.191 | 0.018 | 0.209 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.006 | -0.014 | 0.009 | -0.005 | -0.025 | -0.001 | -0.026 | |

| Cognitive Ability | -0.035 | 0.042 | 0.007 | 0.070 | 0.088 | 0.158 | 0.318 | 0.042 | 0.360 | |

| Family Structure | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.048 | 0.003 | 0.060 | 0.063 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.036 | |

| Number of Siblings | -0.026 | -0.058 | -0.084 | 0.048 | -0.128 | -0.080 | 0.013 | -0.022 | -0.009 | |

| Financial Condition | -0.060 | 0.060 | 0.000 | -0.066 | 0.118 | 0.052 | -0.051 | 0.020 | -0.031 | |